What Are Blueprints?

There’s no such thing as blueprints anymore and haven’t been for many, many years. And yet the term is so ingrained in my profession that hardly a week goes by that someone doesn’t ask me about “a set of blueprints”.

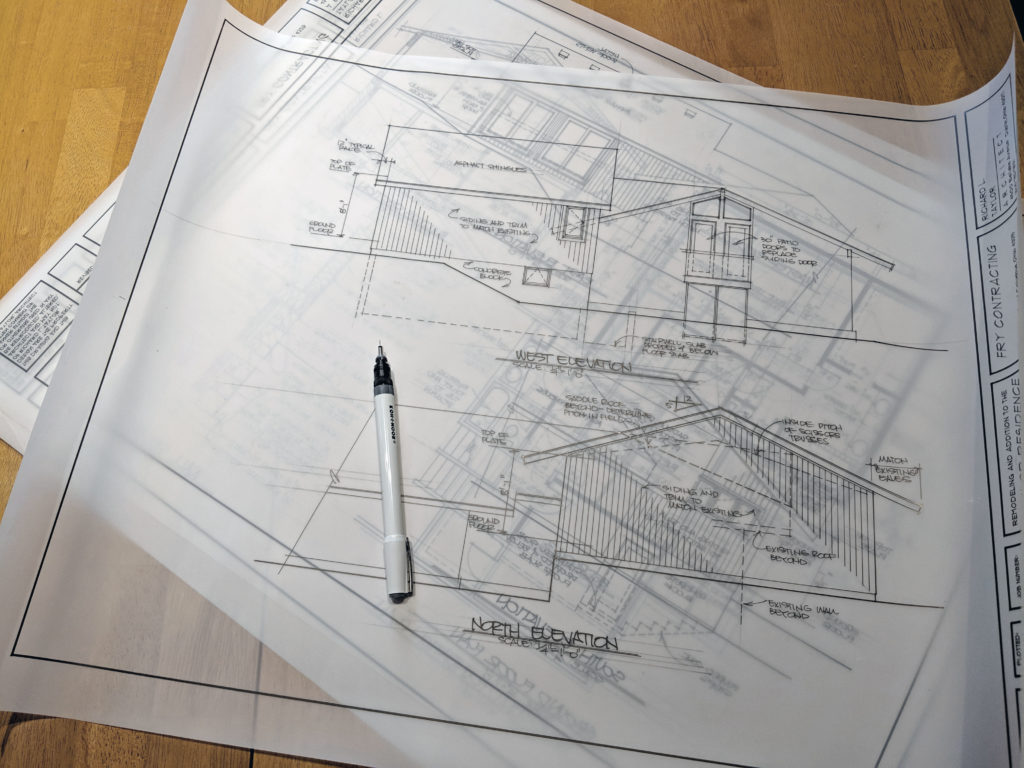

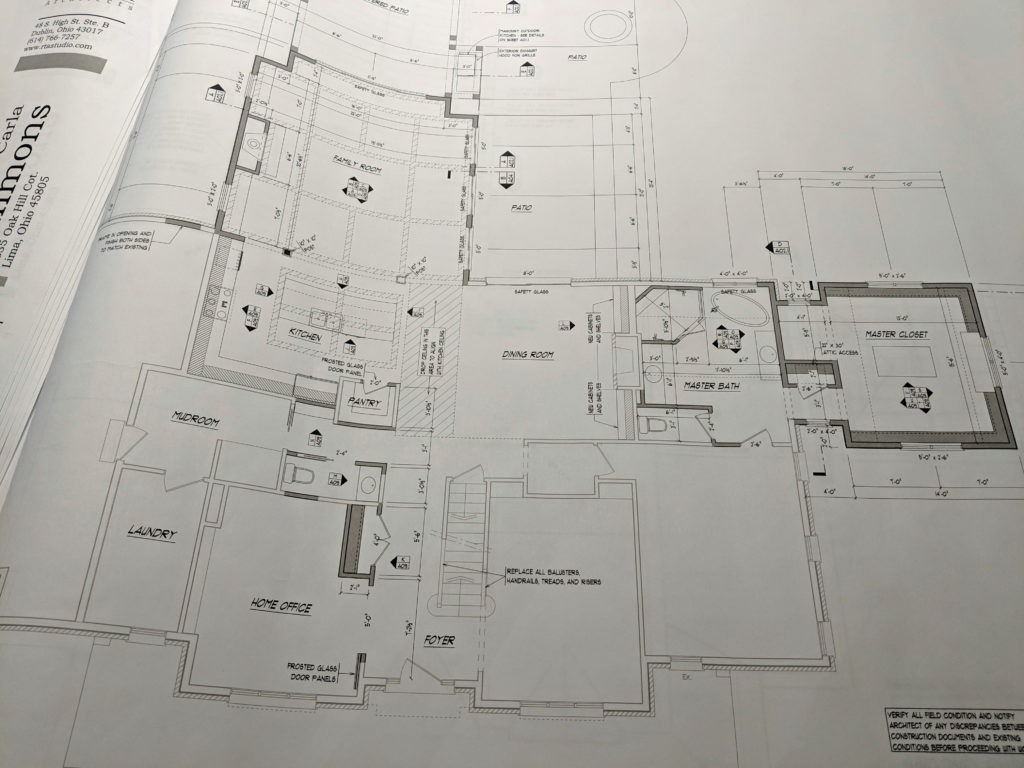

Today Architects just make “prints” of our drawings – essentially giant Xerox copies. (Even those are becoming more rare – more often than not, I email PDFs to clients and contractors).

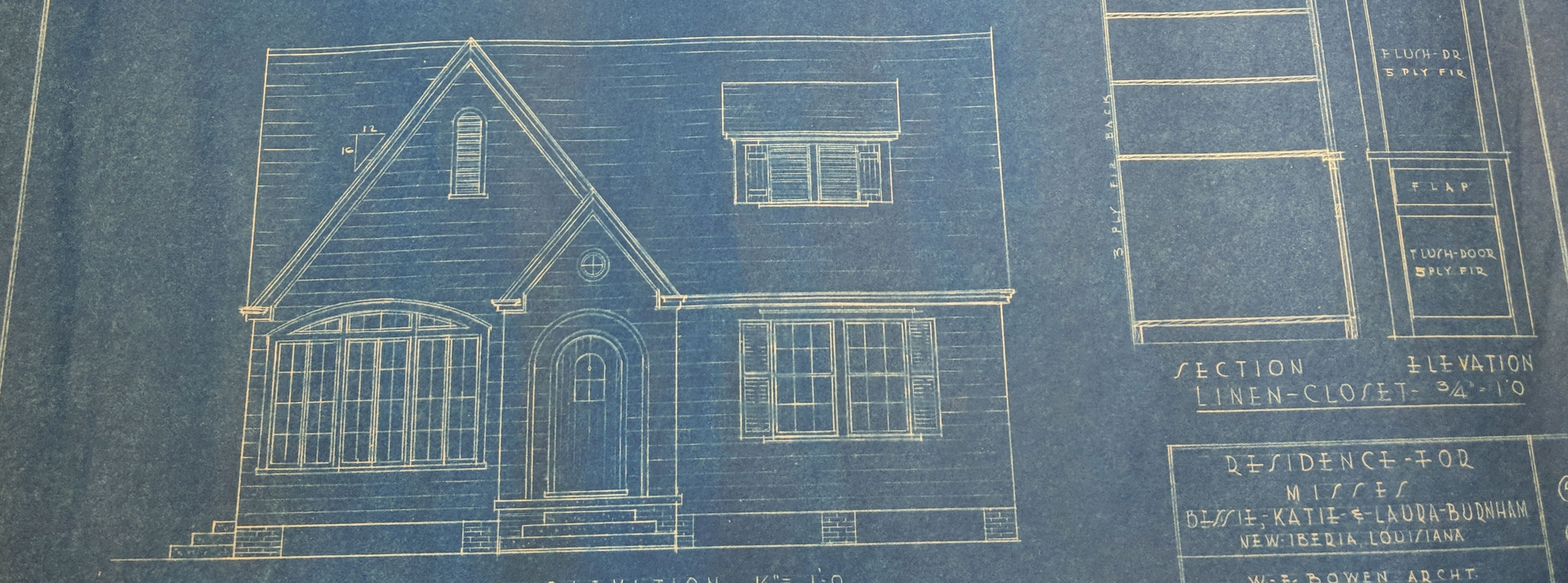

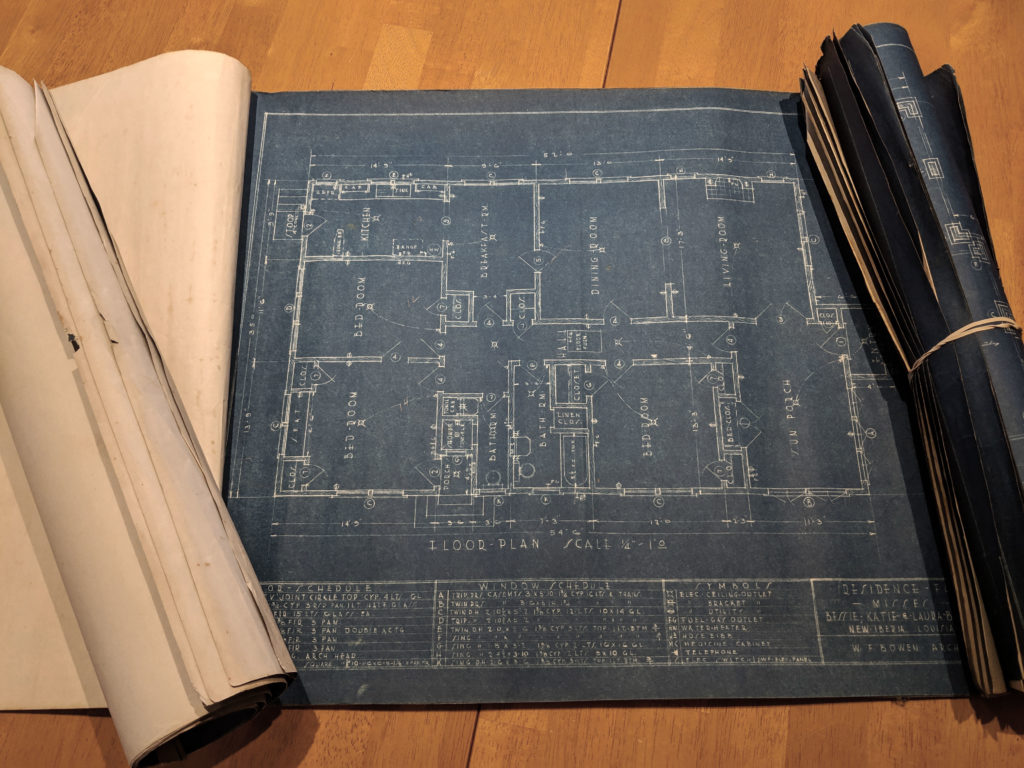

But every now and then, when I have the privilege to work on a home built in the early 20th century, the owner pulls out an old, crumbling, smelly set of true blueprints, like the ones in the photo below.

It seems odd that we once made these “white line” prints – white lines on a dark blue background; what was that all about?

Diazo Printing

When I first began practicing, the profession was already past making “white line” prints, but the technology we used was still rather prehistoric. We made “diazo whiteprints” or “bluelines”, a three-step process that made blue-on-white copies one at a time.

Step one was making the original drawing – at my first job, we did this by hand with technical pens or plastic-lead pencils on translucent vellum or Mylar plastic film. If you made a mistake in the 1980s there was no “delete” key – you erased your work and started over.

Then the original drawing was placed on top of a sheet of yellow paper – the yellow hue was diazonium salt, a light-sensitive chemical – and the two-drawing sandwich was fed into a machine that exposed it to ultraviolet light.

The UV exposed the diazo where it wasn’t covered up by lines on the drawing, leaving a white sheet of paper with the drawing in faint yellow lines.

Finally, that yellow-line drawing was fed into another part of the machine, where ammonia fumes from an attached bottle of ammonium hydroxide developed the yellow lines into dark blue lines.

And then you made the second print.

I had a small diazo machine in my office for a few years so that we could make our own quick copies. Everyone knew when prints were being made – the ammonia smell was so strong it made your eyes water!

That couldn’t have been healthy.

Blueprinting

The old “true” blueprinting process started in the mid 19th century and lasted around 100 years, but it had its problems – prints were difficult to make and required using some fairly nasty chemicals. And marking up a dark-blue drawing required a white pencil – who carries one of those around in their pocket?

Making a true blueprint took six steps: 1) make the drawing on translucent paper; 2) place the drawing over chemically-coated paper and clamp together under glass; 3) place the frame out into bright sunlight for several minutes, until the chemicals are exposed; 4) take the developed print out of the sun; 5) wash away the unexposed chemicals and 6) allow the print to dry.

Is it any wonder we eagerly embraced large-format xerography the moment it became available?

Making Prints

There are still a few Architectural offices with large-format printers on site for quick prints. I stopped making my own full-size prints years ago because my local digital print service delivers my drawings to me almost as fast as I could make them myself.

Of course you can still ask me for “a set of blueprints” – just don’t be surprised when a PDF file shows up in your inbox.